(NOV 27) At the end, Hector Camacho’s last fight was stopped. Not by a referee inside the ropes in a major boxing venue, where, during many “big fight” nights of the last two decades of the previous century, Camacho was a fixture, but by his family, surrounding his bed, in the Centro Medico trauma center in the fighter’s native Puerto Rico. Four days earlier, Camacho had been shot while sitting in a car outside a bar. He had lingered in a coma while his condition and prognosis worsened to the point where he was medically adjudged to be “brain dead”. Hector Camacho was 50 years old and he had lived that relatively short life, both inside and outside the ring, hard and fast. His fans called him flamboyant, his critics, a showboat and the truth was probably somewhere between those two poles of behavior. But whatever one thought of Hector Camacho and the manner in which he utilized that half century of life, it is difficult not be in awe of what he accomplished in the sport of boxing.

Hector Camacho was a New York fighter. Born in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, he arrived, with his family, in New York City in the 1960s, settling in the northeast section of the borough of Manhattan known as Spanish Harlem. Like many youths of that era and heritage, Camacho grew up on the streets and followed his instincts and wits through several minor run-ins with the law, before being shuttled into an amateur boxing program, a historical New York refuge and path away from neighborhood dead-ends for others, in earlier years, with names such as Graziano, LaMotta and Tyson. Camacho prospered in this environment, winning three NY Daily News Golden Gloves titles and turning professional in 1980.

His first sixteen bouts were in his adopted hometown, all wins against the type of opposition that is usually reserved for talented fighters deemed to have a future in the sport. In his thirteenth bout, in December 1981, Camacho won the NABF super featherweight title against Blaine Dickson (15-3) in twelve rounds at the Felt Forum in Madison Square Garden. He defended the title six months later winning in one round against veteran Refugio Rojas (19-10). He was now ready to move onward and upward, out of New York, first to the lights of Atlantic City’s casinos. His bout, at the Sands Casino in New Jersey; against Johnny Sato, set Camacho on his path towards his 85 bout career and multiple world titles. Sato, a tough southpaw from California was to be a good test for the young fighter and his future prospects. Sato went out in four rounds, sending signposts of the fame and fortune out there for this New Yorker. Camacho also laid groundwork for what would be his trademark of flamboyant bravado. Asked about this seminal bout by Sports Illustrated, Camacho remarked, “If I had met Sato a few years ago on 115th Street, I would have done the same thing for nothing.”

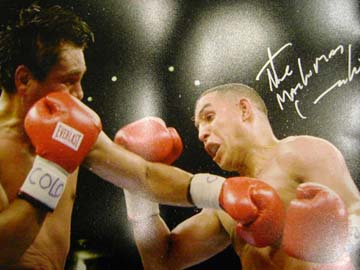

It was a wild ride, in and out of the ring. Camacho had wins over Rafael Limon, Edwin Rosario, Cornelius Boza Edwards, Howard Davis Jr., Ray Mancini, Vinny Pazienza, two decisons over Roberto Duran and a win over Sugar Ray Leonard. He split two bouts with tough Greg Haugen and lost to Julio Cesar Chavez, Felix Trinidad and Oscar De La Hoya. In short, Hector Camacho fought every one who was anyone in the last two decades of the twentieth century and had more big wins than big losses. His “act” from the moment his music started, to his walk back to the dressing room, following the bout, set him apart in an era when many fighters tried for flamboyance and came up embarrassingly short. Hector Camacho’s appeal spilled over the top. There were also arrests and jail time for a theft in Mississippi, restraining orders from his wife and a sometimes strained relationship with a son who, himself, is a world ranked fighter.

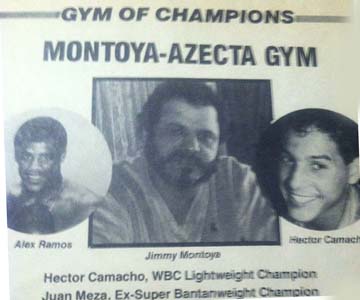

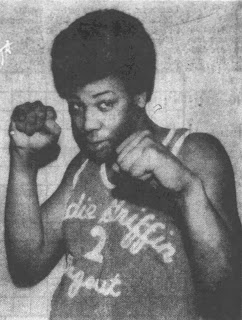

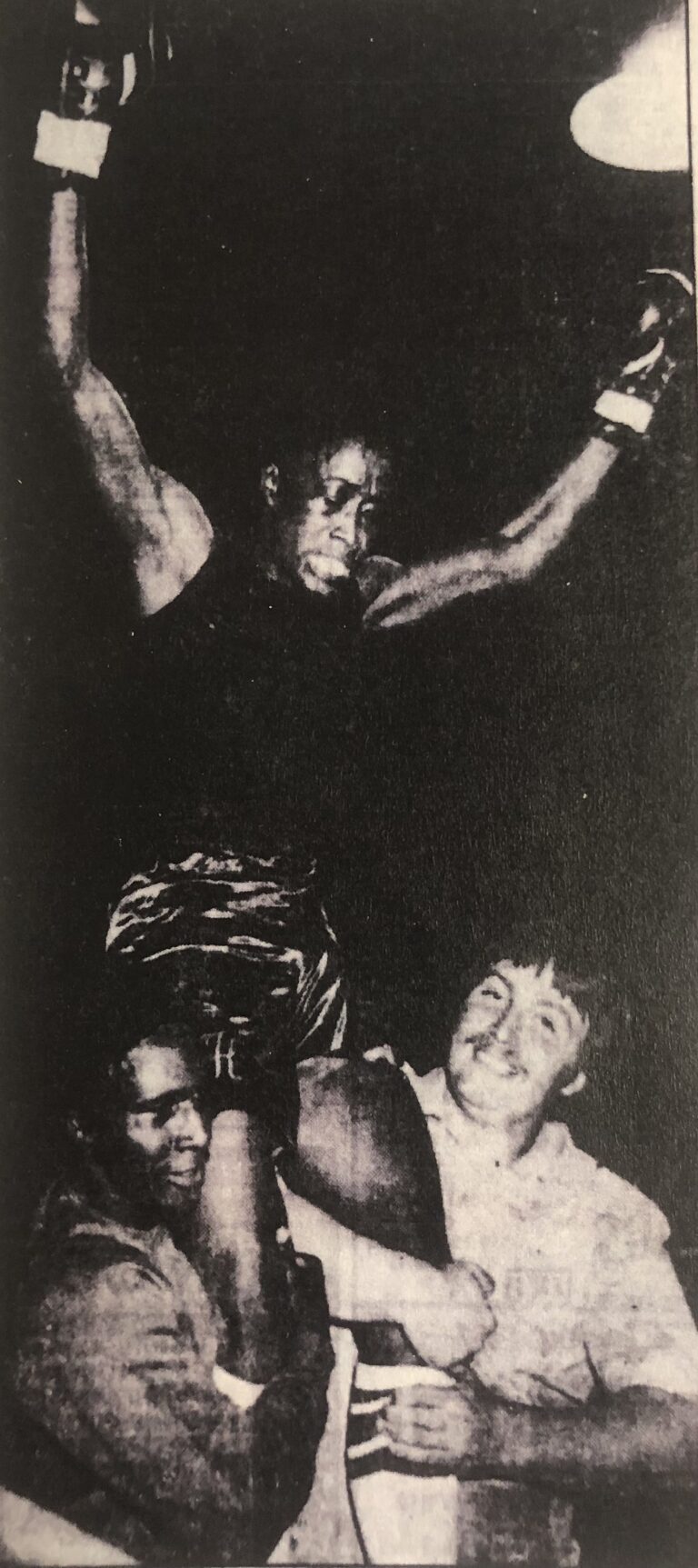

But the sport of boxing and the streets of Spanish Harlem have never been renowned for the output of model citizens. But even here Hector Camacho deviated from the norm. Later in his life, he joined his boxing friend and fellow New Yorker, middleweight contender, Alex “The Bronx Bomber” Ramos (they had known each other since they were 10 and came to California around the same time in the 1980s) in a campaign against urban graffiti, jointly appearing in the acclaimed documentary, “Style Wars.”

Hector Camacho was a very talented boxer who promoted both himself and his sport with almost unlimited energy at almost every opportunity and his sport was much the better for having him as a champion. The decision to take him off life support was, unquestionably, the right decision from a medical standpoint and in another sense, the perfect decision from a symbolic standpoint. Hector Luis Camacho never belonged in the same sentence with the phrase, “brain dead.” There never was a fighter, in all aspects of his long career, who was more “alive.” Remember him for all that he was, good and bad. But honor the memory of what he was in the ring.