The seamy side of female boxing

Deception, fraud tarnish women’s ring

By KEN RODRIGUEZ

January 10, 1999

Permission rights granted by

the Miami Herald to publish.

| A mysterious woman from Atlanta appeared in the MGM Grand boxing ring in Las Vegas two years ago, a shadowy figure amid sparkling lights. She was tall and thin and went by the moniker Foxy Brown, and that should have given fans a clue.

On paper, Bethany ”Foxy Brown” Payne looked like a champ. Fifteen victories in 16 fights, the ring announcer said. But the woman inside the ropes, awaiting the biggest female fight in history, was a former prostitute, a stripper who had never fought before. Within minutes, Payne was hammered by Christy Martin, reigning queen of women’s boxing, and disappeared into a haze of smoke and neon. |

The Martin-Payne match, hyped as a major prelude to the first Evander Holyfield-Mike Tyson fight on Nov. 9, 1996, lasted one round. A record pay-per-view audience of 1.6 million homes witnessed the first round technical knockout.

Women’s boxing, its popularity rising on the grit and glamor of Christy Martin, is propped up by a host of Bethany Paynes, opponents who can’t fight a lick. Some are hookers, many are exotic dancers, most are looking to make quick money.

Once considered a fringe, circus-like sport, women’s boxing has moved into the mainstream since Don King and Bob Arum began promoting its biggest stars. Today, Christy Martin commands $125,000 purses and Lucia Rijker and others appear frequently on national pay-per-view telecasts. Despite the growth, few bouts feature evenly matched fighters. Promoters, in fact, control the outcome of most matches by demanding a steady stream of dead bodies for their champions and contenders to bludgeon.

Christy Martin made $75,000 for beating Payne. According to Fight Fax, Inc., keeper of all professional boxing records, Payne had never before fought in a sanctioned bout. Mezaughn Kemp, Payne’s trainer, pulled Payne off Atlanta’s streets to make $6,000. ”I trained her for 2 1/2 weeks,” Kemp says proudly.

This is a story about the seamier side of female boxing. A story about exotic dancers parading as fighters and one man who trains them. A story about abuse, deception and sex. It is a story gleaned from more than three dozen boxers, trainers, matchmakers, promoters and law enforcement officers — and several police reports.

Among the key figures and revelations:

Dania Beach’s Lisa McFarland told The Herald in a tape recorded interview that she threw a fight to Bethany Payne last year in Tallahassee. Records indicate McFarland and Payne each were paid $400 for the fight, but McFarland says she received an under-the-table bonus of more than $1,000 for tanking the bout.

Atlanta’s Tawayna Broxton, a former stripper, rarely trains more than a day for her fights and has only one victory in seven bouts. Yet she is among the most sought after opponents in the business because she has gone the distance three times with a world champion.

Mezaughn Kemp trains 22 women fighters, many from strip clubs and jails. ”I think I should be nominated for a Nobel Prize for as many women as I have saved off the streets,” he says. Kemp has been arrested three times for sexual misconduct, once for assaulting a female fighter.

Some opponents, like Ohio’s Lakeya Williams, fall at the first glancing blow and remain down for the count, unhurt.

Says Melissa Salamone, International Women’s Boxing Federation junior-lightweight champion: ”There are only two types of fighters — horrible and great. There’s nothing in between like in men’s boxing.”

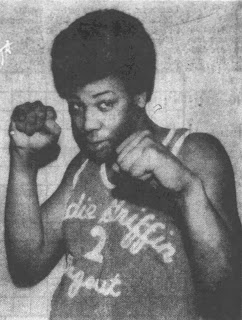

Kemp, 46, trains some of the worst and gets 10 percent of their purses. Some of his more sought-after fighters include Payne (1-7), the former prostitute; Broxton (1-7), the former stripper; and Sherrie Ann Painter (0-7), who told The Herald she makes her living in ”adult entertainment.” Says Bobby Mitchell, a Don King matchmaker from Columbia, S.C., ”The girls out of Atlanta probably carry the biggest reputation. If you want an opponent your girl is going to take out quick, that’s where you go.”

Mitchell ought to know. He arranged the Christy Martin-Bethany Payne fight.

How did Payne, a fighter with no previously documented experience, land a pay-per-view bout against the world’s best known female boxer?

Martin’s original opponent withdrew. Mitchell turned to Kemp, known for supplying bodies on short notice, and Kemp took to Stewart Avenue, an Atlanta strip notorious for prostitution. Says Kemp, ”We got a call for a girl to fight Christy Martin. And I saw this one girl walking the streets and I said, ‘That girl’s got some pretty legs.’ ”

Creative biography

By the time Payne arrived in Las Vegas, somebody had created her biography, noting details of 16 fights, and distributed it to reporters.

After Payne lost, the media reported her record as 15-2. Thirteen of those opponents might not exist. Fight Fax, Inc. has no record of them.

Asked how Payne arrived in Las Vegas with 15 victories, Kemp replied, ”I plead the fifth. I’ve got nothing to say about that. I’ve been known to pull a lot of things in boxing.”

Payne did not respond to requests for comment.

Today, Kemp says Payne works as a dancer and fights when she can. She might be the most successful female fighter alive with a 1-7 record.

Just last year, she fought for a world title.

Lisa McFarland can’t forget. She runs, skips rope, punches bags and spars until her fists are sore and then it happens. The memory reappears and drags her back to May, 31 1997. The phone call. The fix. The money. The shame. ”I was disgusted with myself,” she says.

McFarland, who once fought for Kemp in Atlanta, says she tanked the four-round fight with Bethany Payne — a fight Payne won by unanimous decision.

”The only reason I threw that fight was because, well, at that the time I needed the money,” McFarland, 35, said in a taped interview. ”I wasn’t working. I was putting all my effort into boxing.”

McFarland refuses to identify the man who paid her to throw the fight at The Moon, a Tallahassee night club. Now working two jobs at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, McFarland says she never spoke with Payne about fixing the bout and insists that Kemp didn’t pay her to lose.

Fix denied

Kemp denies that McFarland threw the fight. ”She’s lying,” Kemp said. ”Why would anyone pay her $1,000 to [fix a] fight with Bethany Payne?”

Mike Scionti, executive director of the Florida Athletic Commission, will investigate McFarland’s allegation, but questions her account. ”It’s hard to fix a fight that goes to a decision,” Scionti said. ”It makes no sense. Neither one of them is very good. I’m very, very upset that something like this is even being said.”

How could McFarland throw a fight ending in a decision?

”Second round, I fell,” she said. ”She threw a right, hit my jaw. . . . There was no power whatsoever.”

Heavy training

McFarland, now training five days a week for her next bout, says the fix unfolded like this: Two hours before the fight, the man who offered the bout to McFarland asked her to throw it. ”I smiled and couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” said McFarland, a divorced mother of three sons. ”But I was already kind of disgusted, so I just went ahead and said, ‘OK.’ ”

Five months later, Payne went on to fight Tracy Byrd on national pay-per-view for Byrd’s IFBA world lightweight title. Payne lost. McFarland went on to beat up a couple of opponents.

After a recent workout, McFarland pulled out a pair of black and white trunks, inscribed with words that offer comfort and hope.

”Baby Ali.”

McFarland smiles.

”Kemp gave me that name.”

Mezaughn Kemp once had a golden touch with fighters, a magical name in Cincinnati. He trained former world junior-welterweight champion Aaron Pryor and 1992 Olympic bronze medalist Tim Austin. He guided two sons, Zapata and Keith Kemp, to prestigious amateur titles. He directed a thriving youth boxing program on a $1.5 million budget. He owned two homes, made a lot of money. ”I was almost a millionaire,” he says.

Then his world blew apart. A 13-year-old fighter he trained accused him of rape. As police investigated, another female fighter told of receiving a call from Kemp asking for oral sex. Not believing what she had heard, the girl asked her coach to repeat himself. He did. She hung up.

Evidence mounted. The 13-year-old told of getting paid for sex. A pair of sneakers the first time, $40 cash the second time, $20 the third. A grand jury indicted Kemp. He packed and moved to Atlanta with a dirty little secret: a felony conviction for corrupting a minor.

Not the first time

It wasn’t the first time he had been arrested for sexual misconduct. A 15-year-old girl accused him of rape in 1991, then recanted. The same girl accused him of rape in 1992 but recanted again. His third arrest — the one that ended with a conviction — made the local papers.

”There were several incidents of rape,” Cincinnati police Lt. David Ratliff told the Cincinnati Inquirer. ”We have investigated him previously for alleged sexual abuse of young girls on several occasions.”

Kemp pleaded guilty to corrupting a minor and received a two-year suspended sentence. He was placed on three years’ probation and ordered to attend counseling for sex offenders. Later, Kemp was sentenced to 10 days in jail for violating terms of his probation.

”I was set up,” he says without further explanation. ”I’ve never had any problems with women. A person can get accused of anything.”

His life is a swirl of violence and sex. Strippers. Prostitutes. Exotic dance clubs. Twenty-two biological children. ”I can’t even tell you the names of all my grandchildren,” he says.

Defining moment

Looking back, he points to a shotgun wound he suffered at age 21 as a defining moment. Without going into detail, Kemp says that burst of violence, which ended his boxing career, triggered a desire to help children.

Years later, his legal problems in Cincinnati prompted another change. Kemp quit training men. Quit working with the Aaron Pryors and Tim Austins and devoted himself to female fighters.

Why?

”I try to get people off dope, crack, out of prostitution. This is my therapy.”

Tawayna Broxton waits on tables at Nikki VIP, a strip club in Atlanta’s red-light district. On the side, she does a little boxing. Eight career fights, seven losses. One recent defeat came in a six-rounder in October against Belinda Laracuente at Miccosukee Indian Gaming. Unanimous decision.

”I didn’t train at all for the fight,” Broxton says.

Opponents rarely train more than a few days for a bout, if they train at all. Broxton, 20, doesn’t have the time. She supports a 5-year-old son on $500 a week at Nikki’s, plus an occasional check from a club fight. ”The money in boxing is good,” Broxton says. ”I make anywhere between $400 and $2,000 per fight.”

Broxton used to be homeless and broke. For a while she lived on the streets and sold drugs. ”I never went so low that I sold my body,” she says. ”But I have done exotic dancing. I won’t lie to you. I don’t do it anymore.”

She took a job at Nikki VIP on Stewart Avenue. It was on Stewart Avenue that Mezaughn Kemp found Bethany Payne. It was there that Atlanta police arrested Payne for selling her body. And it was there, at Nikki VIP, that Kemp met Tawayna Broxton.

”How would you like to fight,” Kemp asked.

”How soon can I start?” $2,000 prize

Broxton collected $2,000 for her first bout.

There was another incentive to fight. ”I come from an abusive background — mental, physical, all types,” she says. ”The ring helps me put all the energy into something positive. I’ve lived a life of unhappiness. My mother and father split when I was 2. I got pregnant in high school, and my mother didn’t want much to do with me. I escaped to the streets. My father was in prison.”

Enter Kemp. He led Broxton into the ring and from one exotic club to another. He sympathized as she lost amateur strip contests, told her they were rigged. He promised her money and delivered. ”I need her,” Kemp says. ”I’m getting lots of calls on her.”

With a little training, Kemp says, Broxton could become a good fighter. But boxing is not her dream. Broxton wants to become a recording star. She sang the Negro national anthem, Lift Every Voice and Sing, at an all-women’s card in Boca Raton last year. She occasionally sings at clubs.

”I’m an entertainer,” she says. ”I hope somebody discovers me.”

It’s Saturday night at Miami’s North River Boxing Gym, and Lakeya Williams is about to take a dive.

Twenty-eight seconds into the fight, Melissa Salamone lands a glancing blow to the left side of Williams’ face. Williams crashes to the canvas. Referee Jorge Alonso counts her out. Williams remains motionless. Doctors and trainers climb into the ring.

Fifteen minutes later, after Salamone has been declared the winner, Williams, 25, sits on a folding chair in the back of the gym and smiles.

”I’m not hurt,” she says.

Williams is asked why she lay sprawled on the floor so long.

”That’s part of the game.”

Game?

”I’m not in shape.”

Did Salamone’s blow knock you down? Or did you help yourself down?

”Both. You see, I’m going to get paid whether I win or lose.”

Mowing them down

Williams, from Ashtabula, Ohio, is one of nine tomato cans Salamone knocked over to secure a world title fight. The combined record of those opponents: 6-33. ”A lot of my opponents come from topless bars,” Salamone says.

Miami Beach’s Salamone, a strong, formidable fighter, complains that the woman she beat for the title, Melinda Robinson (7-7), couldn’t box, either. ”She was a step up from the others,” says Salamone (14-0), ”but she still didn’t give me much to work with.”

Despite lacking offensive skills, Williams (0-3) knows how to avoid injury. Others are less savvy.

Katie Dallam suffered a savage beating in her professional debut two years ago in St. Joseph’s, Mo. Sumya Anani, an emerging star who studies holistic healing, landed 119 blows to Dallam’s head, broke her nose and ruptured a blood vessel in her brain. Anani, a lean 138-pounder, scored a fourth-round TKO. Dallam, 5-3 and 173 pounds, left the ring bloodied but standing before collapsing in her dressing room.

In a coma

As an ambulance rushed Dallam to the hospital, Anani celebrated victory without knowing the extent of her opponent’s injuries. Later, as Dallam lapsed into a coma, disturbing information emerged: Dallam was 37, not 26 as boxing writers had been told before the fight. She had never been in a ring before, had received her boxing license the day before the bout and had been in a car accident less than 24 hours before she fought — an accident that left her trainer covered with blood.

After leaving the hospital, Dallam suffered memory loss and considered suicide. She no longer fights. Anani went on to bludgeon Christy Martin, winning a majority decision in a non-title bout last month.

Few women have been beaten as badly as Dallam.

Alicia Sparks is fortunate she’s not one of them. Sparks took her first fight on a few days’ notice. She had never put on a pair of gloves until she stepped into the ring against Diana Lewis last May in Indiana.

”It wasn’t as easy as I thought it would be,” says Sparks, of Indianapolis, Ind. ”I got sick, started throwing up in the ring. I got a bloody nose. Some of my teeth were knocked out. My head was pounding. But other than that, I was fine.”

Fine?

Sparks suffered a second round TKO. ”Afterward,” she says, ”I began to like it.”

Bethany Payne fought again the other day. She lost an eight-round decision to Israh Girgrah, a rising star promoted by Don King. Payne amazed Kemp by going the distance.

”She called me up two days before the fight and said, ‘If anything comes up, I need Christmas money,’ ” Kemp says. The offer came the day of the fight. ”She hadn’t trained in over a year and went straight into the ring.”

Kemp says Payne no longer works as a prostitute. But she still runs into trouble with the law. A case is pending against her for possession of marijuana. In 1993, she pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of prostitution, was fined $300 and placed on 12 months’ probation.

A new favorite

Sophia Johnson has replaced Payne as the favored fighter in Kemp’s stable. A 147-pound rock of muscle, Johnson, 26, came to Kemp from jail on the recommendation of another former inmate, Sherri Painter, jailed on a theft charge. Johnson (1-0) knocked out Painter last month. Before that bout, Johnson had wandered in and out of trouble. ”I used to sell drugs,” she says. ”I’ve been robbed three times and raped three times.”

Sometimes Johnson runs from trouble using phony names. Among the aliases she has given police: Sophia Grant and Anita Brown. Johnson may change her name again. She is engaged to Kemp. ”It was love at first sight,” she says.

Johnson is neither a stripper nor a prostitute, though she was once arrested for solicitation of sodomy. The charge was dismissed.

Like Payne, she’s fighting for money.

Payne made $1,200 for the Girgrah fight, and Kemp’s reputation for delivering opponents on last-minute notice rose another notch. No big deal, he says.

”I’ve got girls who can perform better than they can fight,” he says. ”They should win an Oscar for acting. I’ve got fake blood. I carry it with me all the time. I’ve got the works, man. I can have girls eat stuff before a fight that will make their faces swell up during the fight. One girl is allergic to strawberries. So she eats strawberries before the fight and her face swells up and it looks like she got hit and beat up bad.

”This is nothing new. This has been going on for years. Money can make anything happen.”

Herald writer Ray Glier contributed to this report.